Idyllic Sierra Pack Trip Turns to Nightmare

by Melinda Van Bossuyt

For the first time ever in 20 years, we had poisoned llamas. It was a horrible and frightening experience that could have ended in terrible disaster. I want to tell the story in hopes that it might help others avoid the same experience or at the least be better prepared to deal with it. Before I get into the story, I will tell you now that all our llamas survived. But that was no accident.

An Enjoyable Week

It was the fifth day of our three weeks of llama packing in the John Muir Wilderness of the central Sierras in California. We love our time hiking there each summer and are craving another Sierras fix long before winter is over. We were having a great time. It was pleasant weather, though cold and frosty at night. No problem there. We were camping by a beautiful lake where firewood was plentiful and campfires were allowed. We had toasty warm evenings around a small fire ring and a cozy tent with comfortable beds.

On this particular day after tethering the llamas in the meadow nearby, we hiked to a rock dome a couple of miles south of our camp for a great view and lunch. We had a grand time. Once back at camp which we had had all to ourselves, we moved the llamas over a bit and decided to rest in the tent for a little while. Voices came from the direction of the ridge across the lake. Alas, four hikers moved into the camp around the side of the lake from us. Of course, we did not like the intrusion at what up to then had been our own private retreat.

It was time for some dinner, and, after that, we took an evening hike above our camp to look over the rim for the view of the setting sun. After a bit more exploration, we headed back to camp as it was time to bring the llamas in for the night.

A Group of Fine Pack Llamas

We brought the boys up to camp and put them in some tall wiry grass just above us. We had four packers on this trip. Tehipite and LeConte (also known as Angus) were both five year olds that belonged to a good friend. They were bred and had their early training on our farm. We were taking them out with us for some serious pack experience. Our friend planned to join us for the next two weeks of our trip.

The other two llamas are the core of our pack string. Magma, our stud and lead packer at 11 years old is still rock solid on the trail. He never hesitates. He never quits. He is an excellent role model for the younger guys. Tehipite and LeConte are his sons. The fourth llama on our trip is also a Magma son and a main guy for us on the trail. Goddard is six years old and now has three years of experience. He is tall and lean and powerful, a huge llama. Sometimes he is a little goofy, but that makes him endearing to us for sure.

The Trouble Starts

As soon as we put the llamas on the tall wiry grass, they began to eat it voraciously. We brought them their pellet supplement. Only Magma ate all his pellets. Goddard started coughing like he swallowed wrong. After a bit, LeConte did the same. We decided to move them out of the tall grass thinking that they were choking on the grass. Now they were over to the side of our camp not too far from the tent where I could keep an eye on them.

It was dark. We sat by our campfire and listened to Goddard and LeConte cough and cough. I checked on them periodically, still thinking that the tall grass was to blame. Neither Magma nor Tehipite seemed to have a problem. Finally we went to bed. At 11:00 I got up to check and LeConte was still going at it. He was coughing and spitting all over. Goddard seemed to be slowing down his coughing and spitting. The episodes for him were fewer and farther between.

At 1:00 am. I checked again as the coughing noises were intensifying. Tehipite had started coughing and spitting. His situation was the worst yet. He barfed all over himself. Even in the dim glow of my flashlight on his nearly black coat, I could see it. I checked at 2:30 and again at 4:15 am. Goddard and LeConte had quieted down quite a bit. They still looked green around the gills and rather uncomfortable. You could hear lots of gurgling going on inside their bellies. But Tehipite was still very very sick. Who could sleep anyway with all that loud barfing going on? It ripped at my heart because I so desperately wanted to help them all and to stop their discomfort. I lay in my sleeping bag realizing that this was more than choking on tall grass and that we might have dead llamas by daybreak.

At 5:30 am. I got up for good. It was cold and frosty. Magma rested quietly in his spot. He had never gotten sick. That was the one good thing about the morning.

Fallen Llamas

Discovering the Culprit

Dave got up with me and as soon as it was light enough to see, we went down to the meadow where they had been staked out the previous day to see if we could find something bad that they had eaten. What could it be? After all, we had camped at this spot many times over the years and had many llamas munching out in that meadow.

We searched carefully with our flashlights. We found meadow vole holes about 1.5 inches in diameter with a huge frost buildup around the opening. The breathing of the voles increased the moisture and caused the pretty frosty rings.

Finally, we saw it, a small plant that was growing beneath the grass. It had somewhat shiny tiny leaves. Dave said he thought it looked like something from the azalea family. We realized that we had put the llamas further over in the meadow than ever before due to the fact that horses had been there and eaten down our usual spots. They were fairly close, though not next to, a small dry stream bed. Tehipite had been unwilling to jump that spot and I was not in the mood to force the issue the previous morning. Otherwise he would have been on the other side where Magma was. There was none of the "devil's plant," as we came to call it, in the area where Magma had been. We collected some of the devil's plant for later identification. As the morning brightened we discovered the plant in the vomit the llamas had brought up during the night.

The Culprit

Now What?

I had left the activated charcoal at the truck. That was 14 miles away. We had never needed it in all these years, so I left it behind. My brain started thinking of ways to deal with this crisis. It was warming up, so I suggested we move the llamas down to the meadow (the area without the devil's plant) and give them fresh water. The area they had bedded down in for the night was stinking with vomit and spilled water buckets. Once we had the llamas in place in the meadow we fed ourselves. Then I observed the llamas one more time. Goddard seemed to be finished with his coughing and hacking. In fact, I had not seen him do it since maybe 1:00 am. He still appeared to not feel so swell, but seemed to like being in the meadow.

LeConte also seemed to be a bit better than earlier. He had been sick far longer into the night than Goddard. He lay in the warm sun and rolled around on his belly to get comfortable.

Tehipite was a different story. He was very very sick. He continued to hack and vomit. But he was interested in the water and took some sips. Each time he would hack again.

Creating a Cure

In the meantime, I had a plan. I went on the hill above our camp and gathered chunks of clean charcoal from where lightning had struck and burned trees. I brought it back to camp and began to grind it on a rock mortar and pestle style. Dave understood what I was up to and came and helped me grind. Shortly, we had a considerable amount of powdered charcoal. It was black and pure in appearance. I mixed it up in a small plastic bowl with water. I had my big syringe in my pocket just in case I had to pour it down Tehipite's throat. But my hope was that since he was sipping at water, he would just drink it. It was a thick slurry of black that I held under his nose. Then he stuck his lips in and tested it. He must have liked what he tasted because he started sipping the goop. I was amazed and thankful. I held it for him for quite a long time as he took only small sips and occasionally stopped to cough and hack up more stuff.

While I was holding the bowl for Tehipite, Goddard and Le Conte both pooped and peed normally. LeConte had some of the plant in with his pellets. It had been encapsulated in a sort of mucus sack by his body. After that, LeConte began to eat grass. Goddard was reluctant to eat grass. You know how it is after you have been sick. Neither Goddard nor LeConte were interested in the charcoal gunk I was feeding Tehipite.

Tehipite ate all the charcoal. I was grateful as I believed that was his only chance to get well.

Decision to Move

I felt we needed to hike out as soon as the animals were well enough to travel. I knew it was important to talk to the veterinarian and in the back of my mind it seemed that there was something I was forgetting, something else that should be done in case of poisoning, or something else to watch for. We watched the llamas all morning and had some lunch. At 1:30, we decided to bring the llamas up to camp to watch them while we packed.

Tehipite acted like he felt a bit better. He continued to sip water as we packed. He carried only his saddle which attached loosely so as not to bind his sore tummy. Magma carried the most since he had not been sick and has the capacity to haul a very big load if necessary. It seemed necessary. LeConte and Goddard both carried less than 40 pounds each. They both appeared to feel much better. LeConte was eating normally. Goddard still hesitated about eating and only nibbled a bit.

With the llamas seeming to be well enough to travel, we started out at 3:15. I led Tehipite independent of the string and followed along at the rear. He stopped to poop and pee as we climbed the ridge on the other side of the lake. This was the first he had produced. I was hopeful. It took us 45 minutes to cover the two miles to the next lake where we could stop and camp if the llamas were having trouble. Everybody seemed okay, so we continued on. Just past the lake, Tehipite coughed up a little, but it was minor and he seemed eager to keep going.

After a bit, we tied Tehipite into the string. We hiked about 3.5 miles to a ridge. From there we would descend another 2.5 miles to a meadow where we would camp. At the ridge, Tehipite had another coughing and urping spell which soon subsided. We stopped about a half mile from our intended camp to fill our water bags with spring water. We made it to our camp before 7:00 pm. Not bad for an eight mile hike with sick llamas.

We unloaded the llamas and put them out in the meadow. Tehipite seemed better. We fed no pellets to anyone. Tehipite started nibbling grass! Goddard ate lots of grass. It got dark and we crawled into our tent hopeful that everyone would be well in the morning.

Out to the Trailhead

We got up early the next morning because I wanted to hike out and call the vet as soon as possible. Tehipite seemed much better. He was eating and drinking. We packed up and hauled out of there by 8:15 am. I led Tehipite separately at first. After a short distance, we tied him in the string. He seemed fine. Once again he was carrying only his saddle. We made it the six miles to the trailhead by 11:00. We quickly loaded up and drove to where we could call out on the cell phone.

Instructions from the Vet

I talked to Dr. Debbie at Woodburn Vet Clinic. (Isn't it amazing that I could talk to someone at my own vet clinic while hiking in California?) She said we did the best thing we could by giving the charcoal to Tehipite. She was surprised that Tehipite had consumed the charcoal on his own. She explained that now we needed to watch for signs of pneumonia for about five days. We were to watch for runny noses, wheezing sounds, coughing, and general ill health. This is because of the possibility that the animal aspirated while vomiting. If there was pneumonia, we would have to start a course of antibiotics. She said if nobody got sick by Wednesday, we could start hiking with the llamas again. Watching for pneumonia is what I was trying to remember while back up at the meadow.

Rest and Observation

We dropped the llamas off at Mary and Stephan Biskup's summer cabin near Dinkey Creek. It is at the 5500 to 6000 foot elevation. They have corrals and a 16 acre meadow where they keep their llamas in the summer. We moved our boys into their own private accommodations and I explained the situation with the sick llamas. All llamas seemed to be fine now, but watching for the pneumonia was critical. We sat on the porch and had a nice chat. Their cabin location is such a beautiful place. I hated to leave the llamas, but it was a good and safe place for them to be. We had no place to take them to in the valley except for my parents' backyard. It was 100 degrees down there and the neighborhood was no place for llamas. The Biskup's mountain retreat was a much better place for the recuperating llamas to stay. If there were any signs at all of pneumonia, I could be there in an hour with antibiotics.

I am happy to report that everybody was fine during the critical five day period. We were able to re-enter the wilderness and have a long and enjoyable trip for the remainder of our three weeks.

Epilogue

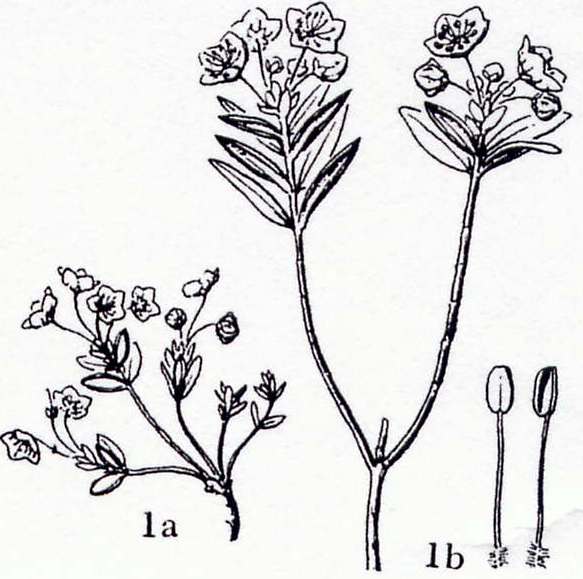

We keyed out the plant once we had the reference books needed. Indeed it was in the azalea or laurel (Ericaceae) family.

Kalmia microphylla

Variations: K. glauca and K. polifolia

Occurrence: Subalpine and alpine mountain meadows and bogs, California to Canada to Rocky Mountains. Also northwest Oregon, western Cascades generally in sphagnum bogs at low elevations.

Poison type: Diterpenoid compounds (grayanotoxins)

Disrupts skeletal and cardiac muscle, nerve function.

- Slow/irregular heartbeat

- Blurred vision

- Paralysis, coma

- Salivation/foaming

- Vomiting, colic

- Labored breathing

- Lethal at 0.2% of body weight

1998 Field Guide to Plants Poisonous to Livestock Western U.S., by Shirley A. Weathers, Rosebud Press.

1973 Flora of the Pacific Northwest, by C. Leo Hitchcock and Arthur Cronquist, Illustrated by Jeanne R. Janish. University of Washington Press.

BACK - HOME

|

Packing, Articles, and Photos

|

|

Welcome to the very bottom of the page! All material on this site, including but not limited to, text, images, and site layout and design, is copyright. Copyright © 1983-2012, Spring Creek Llama Ranch. All rights reserved. Nothing may be reproduced in part or full from this site without explicit written permission from Spring Creek Llama Ranch. All website related questions can be directed to the webmaster or webmistress. Questions about llamas, services, or other such things, can be directed to Spring Creek Llama Ranch.